The first eight weeks of 2022 brought some good news for global supply chains – a gradual decline in container prices and slight improvements in congestion at major ports and inland terminals. But the conflict between Russia and Ukraine that began on February 24 seems to have reversed the direction of change at a stroke.

Taking a look back, we learn that in 2021, 1.46 million TEUs of cargo were shipped by train between China and Europe, a 30% increase over the previous year. Among them, the most important products such as electronics, auto parts, and textiles, helped to alleviate the congestion of Chinese ports in 2021.

Through our logistics partners Chengdu International Railway and China-European Railway, we were able to get an overview of the current situation and gather information on the transport and operating business in China.

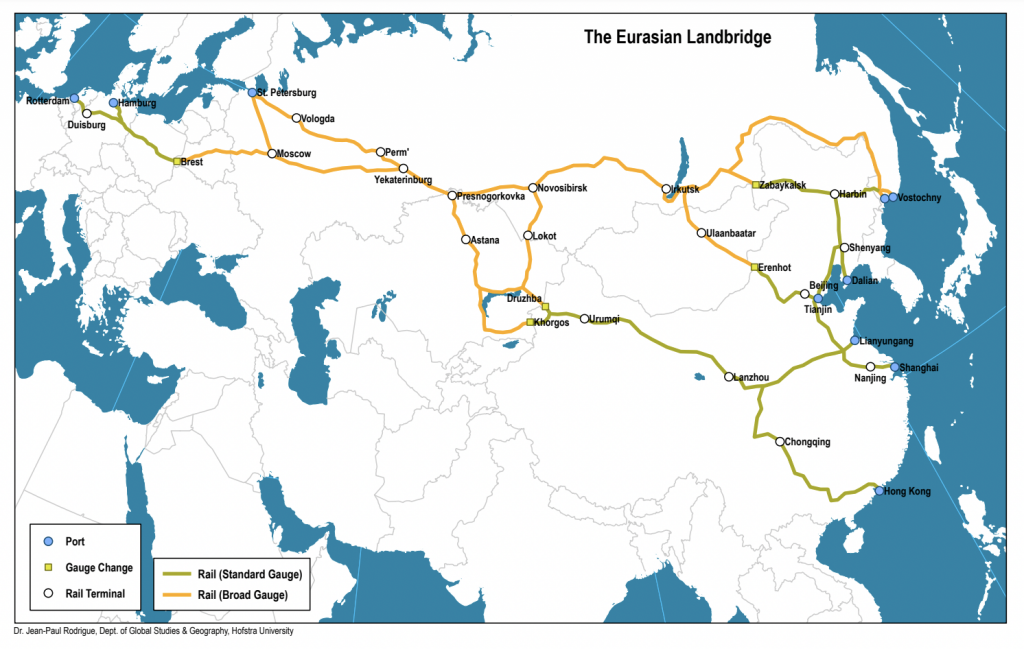

Around 4% of rail freight traffic between China and Europe is routed via Russia (the Trans-Siberian route) and 2% via Ukraine. Since March 7, routes via Ukraine have been suspended, while other routes (including routes via Russia and Belarus) remain in operation, but with the increasing risk of a future blockade. So far, current sanctions on Russian railroads do not apply to goods flowing through Russia.

A month after the crisis erupted, shippers are opting for greater security on the sea routes for goods that were previously destined for the railways. Russia’s invasion is likely to halt the corridor’s remarkable growth in recent years, which has been boosted by Chinese subsidies for Eurasian rail freight.

But what is the long-term significance of the Russian invasion of Ukraine for China’s Belt and Road Initiative? And what are the geo-economic implications for the BRI?

China’s BRI, currently the largest geo-economic initiative with 140 countries involved, is being profoundly reshaped by the Ukraine-Russia conflict. For China, the vast Russian landmass was the most reliable land route to the EU market. Russia, Ukraine, Poland, and Belarus were all to become part of the New Eurasian Land Bridge, based mainly on rail transport. These dreams of land connectivity have been shattered by the Ukraine-Russia conflict.

The China-CEE 17+1 Platform, a BRI cooperation platform between China and 17 Central and Eastern European countries, was already suffering setbacks because of the decoupling between China and the United States. The rapid Western-Russian/Belarusian decoupling and the destruction of Ukrainian infrastructure virtually destroyed any short- to medium-term prospect for a robust 17+1 platform.

In the short term, China needs to get back to fundamentals. Connectivity between China and the EU will have to rely more on good old sea routes, which have proven more resilient than road or rail networks. It is worth recalling that more than 80 percent of world trade is still carried by sea-freight.

Another possibility is that China is bypassing Russian-Belarusian and perhaps Ukrainian geography. The other corridors of the BRI will inevitably grow in importance for connectivity between China and the EU. The Central Asia-West Asia (CAWA) corridor is likely to become more important, as the BRI can bypass Russia and reach Europe by crossing Central Asian countries, the Caspian region, Iran, and Turkey.

The possible reinstatement of the Iran nuclear deal and the recently signed 25-year agreement should already strengthen the role of the CAWA corridor. This process is likely to be accelerated by the Ukraine-Russia conflict. The centrality of Iran’s geography to China and the attractiveness of unsanctioned Iranian gas and oil to the EU – as an alternative to Russia – could enhance Iran’s geo-economic role under current circumstances.

Another option is to continue relying on the BRI’s China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is connected to the Indian Ocean. It is also connected by road and rail (e.g., through the Islamabad-Tehran-Istanbul train) to Iran and Turkey (and thus to Europe). China, therefore, has the opportunity to further integrate CPEC and the CAWA corridor, and to strengthen links between China, Pakistan, and Iran to reach Europe by land.

If both Russia and Iran are to be bypassed, China’s BRI can be linked to Turkey’s Middle Corridor, a geo-economic initiative that encompasses the Caspian region and Central Asian countries. Turkish leaders have regularly touted the potential between their initiative and China’s BRI.